The Meadow is an experiment of sorts. Can we do business in a way that generates enough profit to keep it going, of course, but also enough of something else to make visiting us a meaningful experience? The vision was to be a beautiful place where every single person feels welcome.

Our compact with society is to go "beyond giving back." What this means to us is simple. Be as legit, fair, real with our stakeholders as we would be with our own family. This is our Beyond Giving Back platform:

- Seek out what is beautiful and good.

- Engage diverse people from diverse places with diverse perspectives making diverse products.

- Understand the act of selling as an act of connecting.

- Build community by promoting the people, businesses, and organizations around us.

- Measure the value of our enterprise by its impact on our customers, employees, makers and community members.

We see this platform as holistic, meaning that all pieces fit together to make something greater than the sum of its parts. We create a super duper ultra substance called Belonging.

Beyond Giving Back

The shortcomings of "giving back" and why we think it's necessary to think past this noble-sounding practice.

"Giving Back" is a way for companies and owners of companies (aka shareholders) to support social causes. The good thing about this is it redistributes wealth to the society that made that wealth creation possible in the first place. In some ways then, "giving back" is often really just "paying back." It has become popular, and even expected, to "give back" because we recognize that often there are certain inequities involved in the creation of wealth in the first place.

But giving back has at least one problem. Psychologically, it excuses inequities. I'm giving back, so I feel great about being wealthy. Practically, it reinforces them. Amassing fortunes remains socially acceptable. I'm giving back, so what do you have to complain about? These arguments might have some weight, but for the fact that wealth inequality is accelerating at an truly insane rate. Oxfam reports that billionaires worldwide saw their wealth grow by 12% while the poorest half saw its wealth fall by 11%. It seems the giving isn't happening nearly as fast as the getting.

Nobody needs to remind us that wealth inequality is a serious problem today. One of the most bandied-about and mind-blowing statistics in circulation these days comes from Oxfam, a global nonprofit confederation committed to ending poverty. The world's richest 26 richest people own as much as the planet's 3.8 billion poorest people. The challenge with this analysis is that it is so preposterous that it leaves us utterly numb to its true implications. What does 3.8 billion people look like? We get that there is a 3.8 followed by a large number of zeros of people with only a handful of numbers in their net worths. That's easy to imagine: it looks humble, and challenging. Challenging finding a clean drink of water. Challenging putting a pot of food on the table. Challenging making any improvement to these challenges.

We also get that there are a small number of people with large number or zeros after their net worths. ($1,400,000,000,000) What does the wealth look like for these 26 people, on average? That's harder to imagine. Here are three attempts.

Attempt 1: I've always fancied a Bugatti Chiron. It has 1,500 horsepower (that's as many horses as ten late-model Honda Civics) and recently shattered the seemly impossible 300 mph mark. Besides being literally 2 times faster than a California highway patrol car, they are really, really cool looking. The speakers have diamonds in the membranes--seriously. You and your 26 billionaire friends could each own 17,960 brand new Bugatti Chirons. Ok, so that's not really possible to imagine, though we do know for sure that little Susie is getting a graduation Bugatti, whether she likes it or not.

Attempt 2: The median home in America costs $200,000. The price of a really, really nice pair of Bombas socks is $16. You and your 25 other top billionaire buds could each buy 269,209 homes to put your all your stuff in. Then each of you could sleep in a different house, every single night, for the next 737 years of your life, and every morning, wake up and put on a brand new pair of really, really nice socks.

Attempt 3: If you were one of these 26 really, really rich folk, you could set enough money aside to live like Louis XIV, buy just one Bugatti Chiron, and then fly in your private jet to Uganda. There, you could visit a nice open-air market, where you meet a couple, and learn they are working crazy hours in rough conditions yet heroically paying for school for one child and medical expenses for another. You are invited to their home to sip home-made Waragi, and are smitten by the goofy familiarity of the father, the wry wit of the mother, the brooding questions of the daughter, and the giggly hilarity of the son. You scrimmage a little soccer with the father and the daughter, then huddle with the mother and the son over homework. Afterwards you offer to pay for the dinner for the family that night. You crash at their pad, then then wake up and buy them all breakfast the next day, and then lunch. The three meals for four people set you back 36,000 shillings, which converts to $9.75. You barely noticed the expense, so you decide to pay for their meals for a week so they could put their scant resources toward their children’s other needs—but then you realize this is silly, so you go on to put them on autopay, and cover all their meals for a year. A creature of habit, you never bother discontinuing it, so you end up paying for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for this family of four for another 70 years. Meanwhile, still a creature of habit, you visit another Ugandan family, and another, drinking beers and playing soccer and puzzling over homework and crashing at their pad and then buying them all they need to survive for the rest of their lives. Along the way you convince your friends, the other 25 other richest people the world, to do the same. You and your 25 Louis XIV lifestyle-living friends could each do this every single day for seven lifetimes. After you had lived seven lifetimes, you and your friends would have fed 5,218,526 families of four for their entire lifetimes. The health, education, prosperity, and happiness of 20,874,104 goofy witty brooding giggly people would be profoundly altered. Over the course of your gloriously philanthropic jet-setting seven lives you and your 25 Bugatti Chiron carpooling chums would have marveled at your growing sense of shared humanity, and at the improved circumstances of millions of souls. And you'd still top the word's 0.1% wealthy list.

That's what 26 individual human beings hold, largely untouched, lurking within their unobtanium Amex cards. And there are 2,174 other billionaires on earth worth eight trillion dollars. There are many, many more folk out there with mere hundreds of millions. Imagine...

But the trick here is we mere mortals with one life to live and give think in terms of stuff like food and socks and Netflix subscriptions. For a hilarious clue about how myopic our perspective think about automotive reporters who get the sweet assignment of reviewing the Bugatti Chiron. The reporters, I kid you not, will invariably count its gas mileage as a negative. 9 mpg city, 11 highway. The reporter is obviously completely delusional if he or she thinks that this performance is a negative. When you buy a $3 million car that moves 440 feet per second and has diamond speakers, you don’t just want your fair share of the world’s limited supply of 98 octane gasoline, you demand it.

Normally money is something you have and I have, and we use it to transact with one another on a remarkably even and equitable playing field of a free market. But when money is at scale, and when is concentrated, stops being a kind of stuff that buys stuff. It transforms into something else altogether. It become power. Incredible power. The power to write laws, stake out territories, control other people, extract their resources, send men and women to war where they will kill other human beings and/or die and/or suffer trauma. And that's just for warm-ups. Then they pull the plutocrat's version of dine-and-dash, leaving you and me and the family in Uganda with the check to cover all the militarization, environmental degradation, wealth inequality, civic instability, and myriad other impacts. In short, vast wealth inequality translates into a world where individuals, not societies, determine what is best for society, and who will pay for it.

The Meadow

Which brings us back to The Meadow. A shop made with reclaimed wood from a salvage business down the street, with buckets of fresh cut flowers out front, and an embarrassingly obsessive collection of little jars of craft-made salt inside and a sticker on the door saying "We're sipping suds at the brewery across the way. Come get us if you want anything!"

Before we opened, we knew which way the trade winds were a-blowin'. Mega-marts were gobbling up entire swaths of Mainstreet USA and converting all the independently-owned, diversely-supplied, personally- and expertly- serviced small hardware stores, convenience stores, clothing stores, and one-of-a-kind stores. into savanna-sized discount outlets for standardized products spat out of global supply chains. At the same time e-commerce was growing at a fantastical rate, severing the already fraying connection between nature, maker, seller, and consumer.

The Meadow was built on the hunch that people want something better than that. Over time, we began to put words to that betterness. We'd say "our shop feels like coming home," and while we knew that we didn't know what, exactly, that meant, we knew it felt true.

The word I've come to feel expresses our value proposition best is "belonging." Belonging is a core human need, and we live in an age of growing fragmentation, isolation, and even alienation. If we can create belonging, then we have something valuable to offer.

Which brings us to today, and how we've turned our ideas into actions. We express belonging by keeping a shop that is made by hand. We tend to it every day with fresh cut flowers, continually renewing a beauty that suffuses the air you walk through. We offer up virtually no signage because signage tends to get between a shop guide and a visitor. We fill the shelves with a passionately curated collection things that are simultaneously little-known and elemental. Salt. Chocolate. Bitters, Vermouths. And we take the unfamiliarity of these products as opportunity to tell stories as diverse as the visitors who walk through our doors. A female distiller in Holland, migrant farmers in Ghana, craftsmen in Vietnam. When leave our shop, the world around you feels simultaneously more connected and more exotic.

The business of belonging is pretty brass tacks: one-on-one time with customers; products sourced as directly as possible from people whose vision and craftsmanship we admire; employees paid not just in wages, but in the benefits that provide security and dignity--and the occasional travel together to some insanely rad place; lectures at local schools and national museums and international events; with participation (in hours, in dollars) in social organizations baked in to our place, products, and people. "Belonging" is what unifies all this.

Stakeholders

We didn't really think that much about it at the time, but by putting customers, suppliers, and employees first, we were serving The Meadow's "stakeholders" even when cost its shareholders. This kind of practice has hardly made us pioneers--around the world there are entire economies built on this kind of business--but it has given us opportunities to advocate for a kind of business that sees itself as the beating heart of community.

We hear more and more about this kind of vision. Customers are demanding more and more from the businesses they patronize. Employees are demanding more and more from the businesses they work for. Companies are demanding more and more from the suppliers they buy from. Even (some) shareholders are demanding more than just shareholder return. Each of these stakeholders are seeing themselves for what they are: participants. Stakeholders are the new shareholders.

Gargantuan corporate powers are starting to feel a bit itchy under the collar. They've noticed that the classic idea of business as an amoral and mechanistic system for grinding profit out of everything in its path is irksome to some. The previously naive values of little companies like The Meadow are noted.

Slowly over the last decade, and now suddenly these recent months, it seems almost as if a new corporate world order might be taking shape. When you start seeing frothy press releases declaring a shiny new "Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation" you know the times, they are a-changin'. Or pretending to. These corporate powers are not visionaries. On the contrary, they are the most reactionary. If you are a bigshot CEO, you see the writing on the wall and understand that if you don't create some kind of shiny new "statement of purpose of a corporation" soon, then at best you'll seem out of touch, and at worst you'll be left behind. And down go the profits. And out your ass goeth thee, along with all your juicy stock options and eight- or -nine-figure bonuses.

CEOs Rule

A whole herd of Mike Wirths and Jeff Bezoses and Mary Barras and Jamie Dimons have jumped on this Statement on the Purpose, inking their names below bullet points on "investing in our employees" and "dealing fairly and ethically with our suppliers" and "supporting the communities in which we work." You gotta give them props for sticking their necks out and throwing down with some revolutionary ideas.

To read into their Statement of Purpose generously, the new capitalism espoused by these mega-CEOs is striving to advance something more wholistic. Capitalism with a Happy Face. "Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country."

It's pretty hard to argue with that. It makes me feel a little like all stakeholders are created equal. We matter, and by extension, we have rights. I like that.

But it turns out some stakeholders are more equal than others. Wirth's Chevron banked $2.9 billion profit in an age of melting ice caps, home-destroying wildfires, and acidifying oceans. Bezos's Amazon booked $11.59 billion while employees took home $15 an hour and the CEO sat on a net worth of $189.2 billion. That's 189,200,000,000, to give the zeros their due. (That's one and a half times more than all the beer drunk in the Unites States of America in one year.) Barra's General Motors banked $6.581 billion as it idled American factories and became Mexico's largest auto manufacturer. She took good care of herself though, taking home $21.6 million while overseeing a dominion in which her workers earned just 0.41% of her wage.

Even those providing the fuel for capitalism--lenders and investors--make it hard to believe they see value in serving diverse stakeholders. Dimon's Chase Bank socked away a respectable $36.4 billion in a single year while proudly topping Forbes's banking "Dirty List" for funding fossil fuels. Dimon's company also puts profits over principle, people, and even a basic sense of propriety in other ways, denying black and latino people home loans in Washington (26% and 18% of whom were denied loans compared to 7% of equally qualified whites). Dimon's company dodges anti-redlining laws in dozens of other cities by operating closed offices that fail to lend in low- and moderate-income areas as prescribed by law, and instead funnel the bank's wealth into the strategic gold reserves of the wealthy.

Some stakeholders (those that hold shares) seem to get whole continents of cash piled on them while other stakeholders (polar bears, migrants, racial minorities, employees) seem to get... well, not so much.

Let's call a spade a spade, not a gardening tool. These are big corporations. We expect them to act like big corporations, and the scale of the bigness gives us little choice but to accept it. Exxon-Mobil, for example, did not erase a well-documented, 40-year-long history of climate change denial by simply signing the Statement, and it can give you 14.3 billion reasons why it doesn't need to.

We can't really blame big corporations for putting their signatures to statements meant to make us feel better. And rather than point out what hypocrites they are (which I could not resist doing above, sorry) and rather than pointing out how high fallutin' and perfect I am (my company, my leadership, and my own humanity are definitely works in progress) we can simply pause and ask a question:

Is it even possible for stakeholders to assert a rightful place at the table amongst shareholders, or is it an immutable fact of life that stakeholders will always be fed scraps at the feet of their masters? On the flip side, is it reasonable to expect shareholders to just "do the right thing" and invite stakeholders to a respected and equal position at the table? In a world that seems powerless to slow, much less stop rapidly increasing wealth inequality, why would they want to?

The Shares We Hold

Paying taxes is how you and I are invited to sit at the table. It's how we support each other financially, and fund the machinery that connects and nourishes our nation and our communities. But... what's this? The big corporations are not among us! They are over at the buffet eating canapés while we, again scavenge leftovers. A shining example from one believer in capitalism with a happy face is Delta Airlines, which took billions in coronavirus bailout money while also luxuriating in a -4% effective tax rate in 2018. By the way, Amazon, Chevron, and GM also enjoy this magical state of being preposterously profitable and yet negatively taxed. So much for "supporting the communities in which we work."

That the economic power and political power held by big corporations has simply gotten out of hand is hard to dispute. These corporations don't dispute it. High-minded Statements of Purpose reveal that these companies are well-aware of the absoluteness of their power in the global economy. They have no intention of giving it up. So they volunteer a sort of parable to us with words that are just barely connected enough to reality that we believe them--they sort of take the edge off that creepy feeling that our world is controlled by impossibly massive bank accounts exerting impossibly powerful force on the world around us. Black holes warping, then gobbling up time-space.

Which brings us back to wealth inequality, and what we do about it. The biggest challenge I can see to changing things is that the concepts of "capitalism" and "wealth" enjoy near universal veneration. To say you are un-capitalist is to say you are un-American. To say that you are anti-wealth is to say you are a fool or a hippie idealist thawed out after cryogenic napping since the 60s.

Another challenge is that if you do business in America, you are probably a capitalist yourself. Speaking for my self, I have loans and credit cards. I fantasize about finding investors and opening shops in my favorite neighborhoods in Cleveland, Birmingham, Detroit, Eagle Rock, and Charleston. I'm a capitalist. And while I don't actually want a Bugatti Chiron, I would sure love another zero in my bank account so I could stop worrying quite so much about college and rent and what will happen to me when I'm old or injured in a spelunking incident.

Rather than disavow capitalism, maybe we can look beneath it. Shareholders are not the (sole) problem. The problem is that stakeholders are not invited to the party. There are as many ways to invite people as there are leadership styles and company missions. It's both a personal opportunity and a strategic one.

The Meadow looks at this opportunity in ways that are summed up at the top of this article. If we are fortunate enough to make it though the months and years ahead we may indeed try to grow again. Open new shops, bring more voices to more peoples' stories. If we do do that, we will need to make growth more than Capitalism with a Smiley Face. We will need to bring everyone to the party: neighbors, employees, and if you're interested, you too.

In conclusion

If we can bring modest but beautiful shop to a new neighborhood, strike up meaningful relationships with the makers in the community, bring in other products and their stories from around the world, use all of that to spark excitement and connection around the joy of food, and then share humanity and money with the community, maybe we can create interest in a new alignment around the institutions and values of wealth.

"Beyond giving back" is not a solution. It is the idea of seeking balance, not power. How we do this may be different for everyone. But in one regard it is the same for all of us. If we find ourselves in a place of giving back to some of the planet's billions of desperately needy, we can recognize that this only came to be because of inequities that create so much desperate need in the first place.

Mark Bitterman

Owner & Selmelier

The Meadow

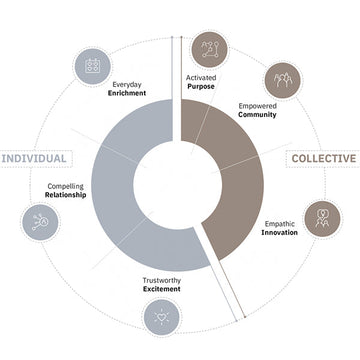

Article. The graphic at the head of this writing comes from an article by IBM. Basically, the author contemplates how to can make a buck off the fact that people gotta belong. But it isn't superficial, and provides a model for parsing the respective roles of the individual and collective aspects of society. All you have to do to take away some value from this article is ignore who wrote it.*

The Business of Belonging.

Book. Waiting in line to hop a ferry, I ran into a remarkable guy. He had been a headline presenter at the conference I was leaving, and had been struck by his vision for investing in companies that aligned with a certain progressive vision for the world. We ended up traveling together for 23 hours. He was eloquent about how technology could address the existential issue of climate change. And he shared with me that all his work notwithstanding, he didn't see how we were going to fix the yawning abyss that is wealth inequality. This is the book he was reading. And it is the book that I have read and kept on my bedside table for over a year now. A Finer Future : Creating an Economy in Service to Life

*IBM's effective tax rate in 2018 was -68% after taking $1.4 billion in government subsidies over the years and pursuing dubious tax dodges like sheltering income overseas.

Which brings me to "Giving Back." The modern conception of philanthropy was more or less invented by Nelson D. Rockefeller, a man who personally owned 1.6% of the entire domestic economy in 1937. Rockefeller was thoughtful in the spending of his wealth as he was ruthless about creating it. The basic idea was that he funded processes and institutions what would execute his vision for improving the affairs of the things he wanted improved. Very brilliant, and very lasting. Today, virtually all giving follows this basic model. Make money. Give a little bit back. Make yourself look like a beneficent god in the process.